War Precautions Act 1914 –1915

How much freedom is appropriate in a time of war?

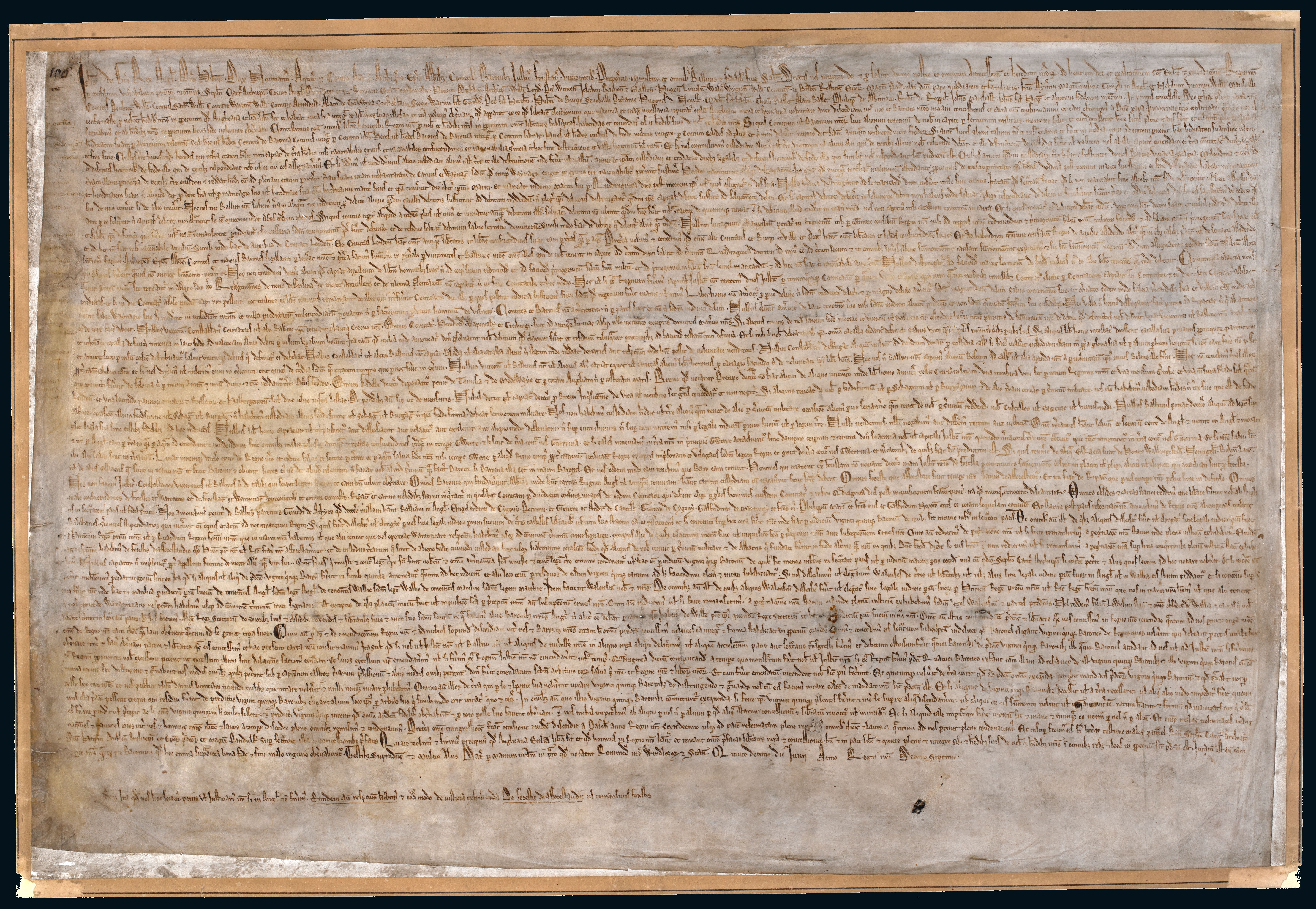

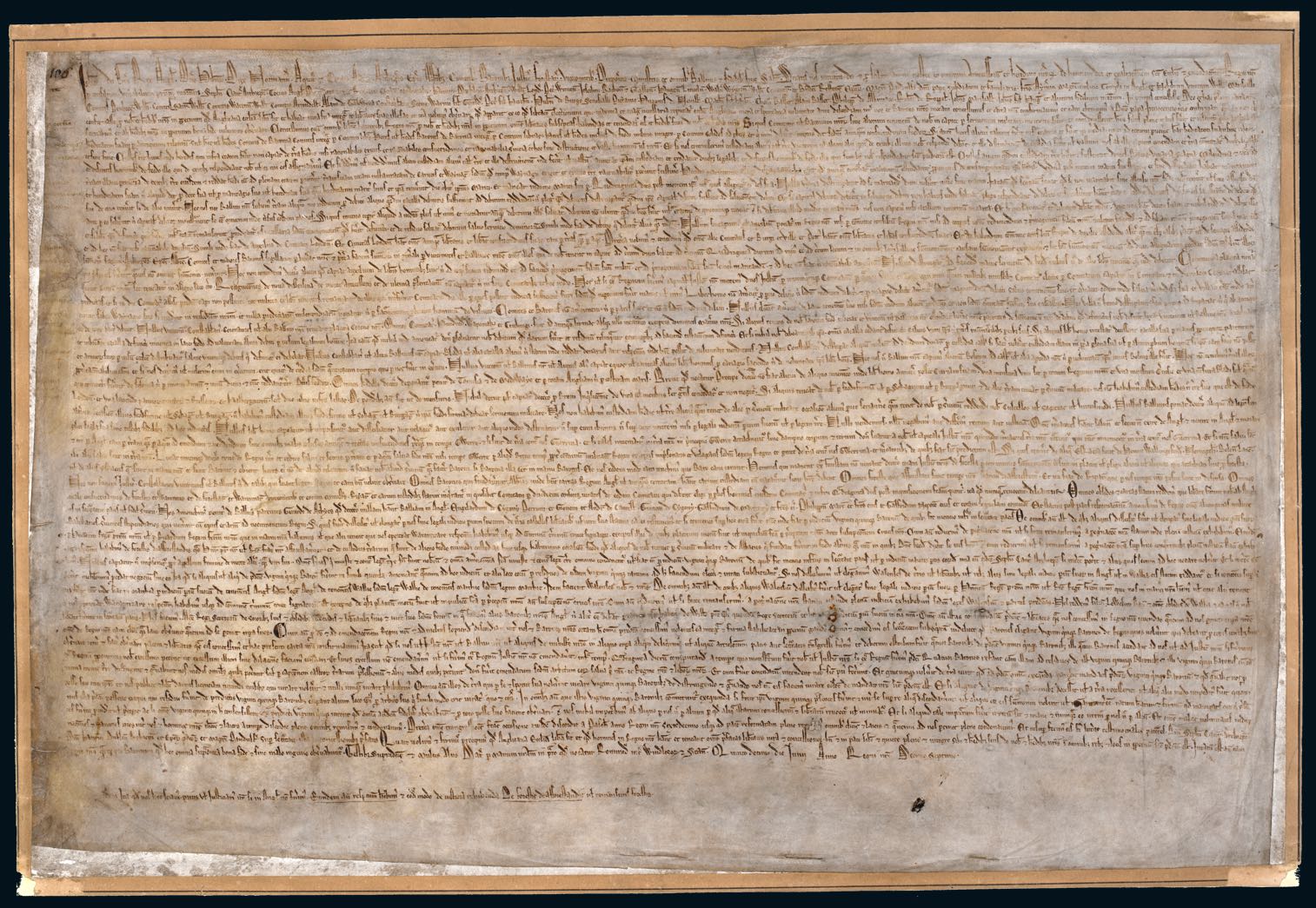

‘To all intents and purposes Magna Carta was suspended and [Prime Minister Hughes] and I had full and unquestionable power over the liberties of every subject.’— Sir Robert Garran, Solicitor–General, 1958

In late April 1915, while the Anzacs were landing on Gallipoli, a battle royal was playing itself out in the Australian Parliament over a new War Precautions Bill which sought to amend the War Precautions Act 1914. The attack on the Bill was led by three members of the Hughes Labor Government: Frank Anstey, King O’Malley and Frank Brennan.

The government had used its defence powers, granted by the Constitution, to draft a Bill empowering it to silence, imprison or deport people considered to be actively subverting the war effort. But, as Anstey protested, ‘There has been no justification for the suspension of civil law and trial by jury … we are simply being swept away by one vast tide that is overwhelming our ideas of human rights and liberties.’

There is an unmistakable irony here. The Australian Constitution empowered the government to counter threats to the rights, freedoms and liberties whose foundation lay in Magna Carta. Yet the powers proposed by this new Bill would have meant that ‘to all intents and purposes Magna Carta was suspended’, as Solicitor–General Sir Robert Garran later put it.

Despite these protests, the Bill became law. It was upheld by the High Court, and was widely supported by the general public. But the question over precisely how much freedom could be guaranteed during a war to safeguard democratic freedoms defied easy resolution.