Darryl Kerrigan

Administrative Appeals Tribunal member: ‘And what law are you basing this argument on?’— The Castle (Frontline Television Productions, 1997)

Darryl Kerrigan: ‘The law of bloody common sense! … You can’t just walk in and steal our home! … You can’t buy what I’ve got!’

Owning land has always been one of the foundational aspirations of Australian people.

During the gold rushes of the 1850s the young self–governing colonies were almost overwhelmed by the demands of newly arrived miners to have the right to buy cheap land to live on. By the 1880s the expanding train networks radiating out from the capital cities, and the spread of wealth throughout society, meant that colonial Australia had more home–owners per capita than anywhere else in the world.

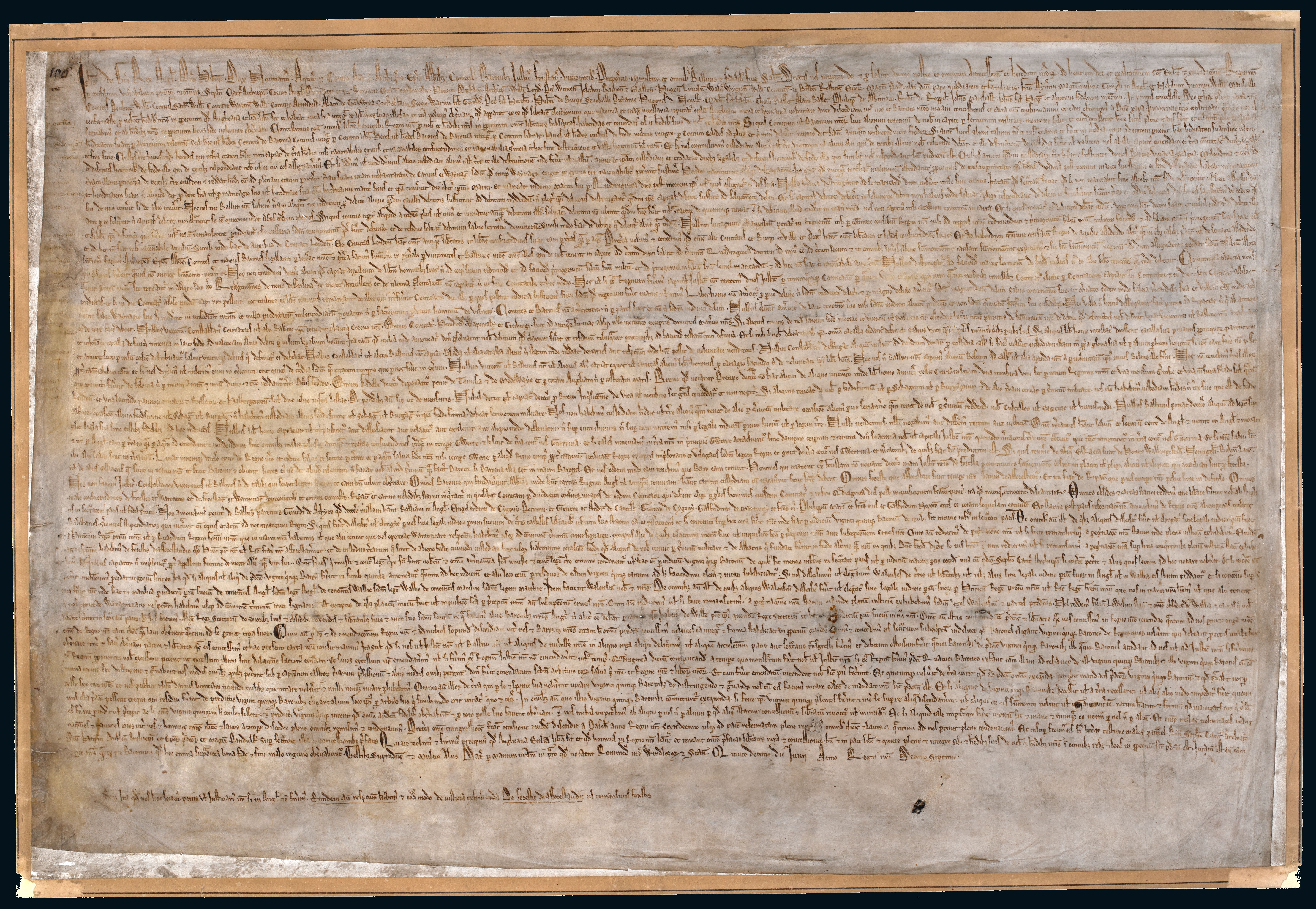

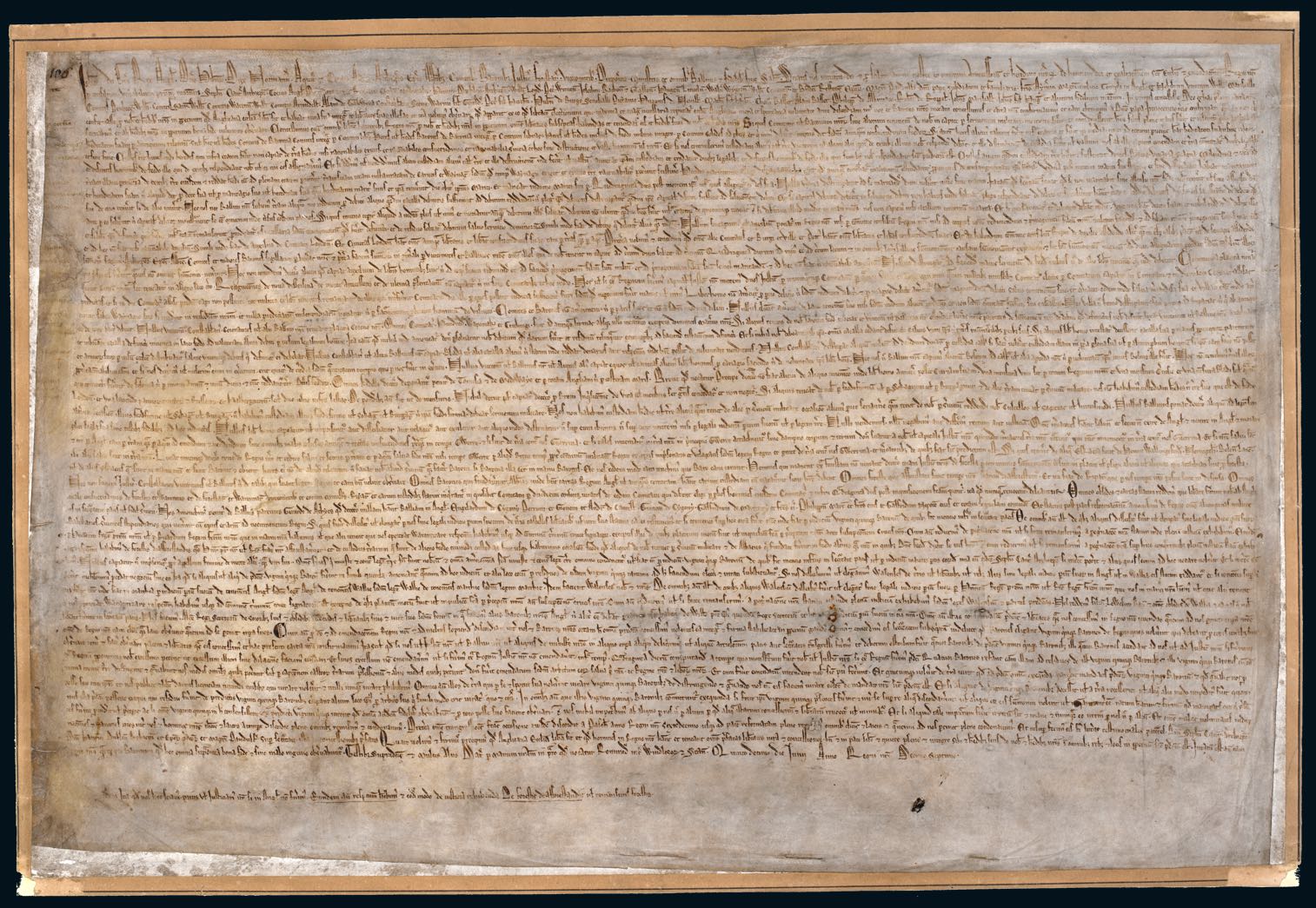

So when, in the 1997 film The Castle, the character Darryl Kerrigan told the Administrative Appeals Tribunal that he was basing his argument to protect his home from compulsory acquisition on ‘the law of bloody common sense!’, he was relying on a tradition more than two centuries in the making. As far back as 1215, too, Magna Carta had included previously unwritten customs concerning property rights and transactions: that property could not be taken without the owner’s consent, or without compensation.

Today this is echoed in the section of the Australian Constitution upon which Kerrigan’s barrister relied in the subsequent High Court case: Section 51 (xxxi), which gives Parliament the power to make laws for property acquisition on ‘just terms’. And while in real life owners may be powerless to stop the compulsory acquisition of their properties, the Constitution at least sets boundaries on the government’s actions — boundaries similar to those set by its legal ancestor, Magna Carta.