A new colony

British subjects denied British laws and liberties

‘Who ever heard of the foundation of a state, dependent or independent, without a power in it to make laws?’— Jeremy Bentham, philosopher, jurist and social reformer, 1803

In founding the first modern settlement in Australia, Home Secretary Lord Sydney raised eyebrows when he opted for a penal colony that would be run according to civil rather than military law.

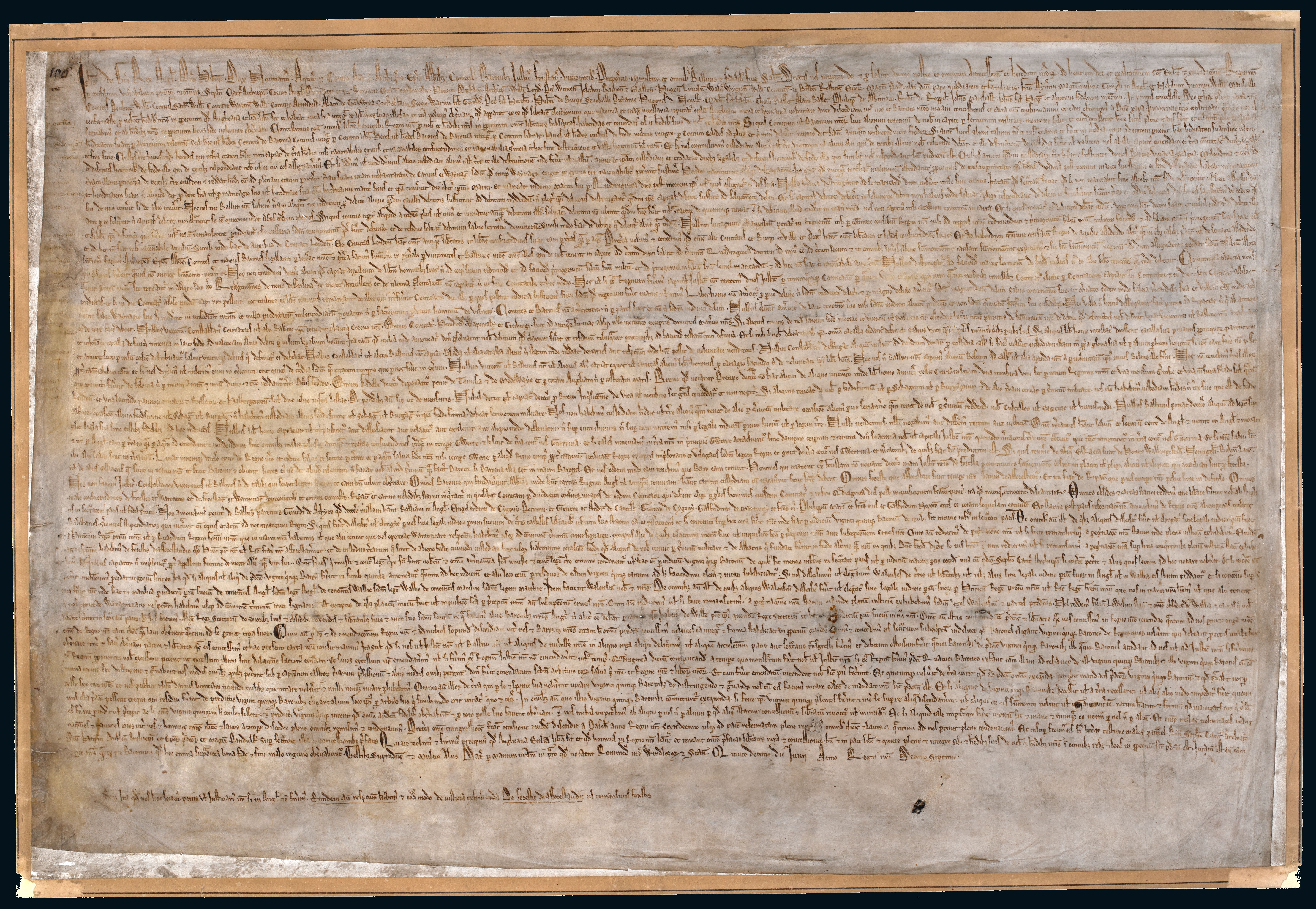

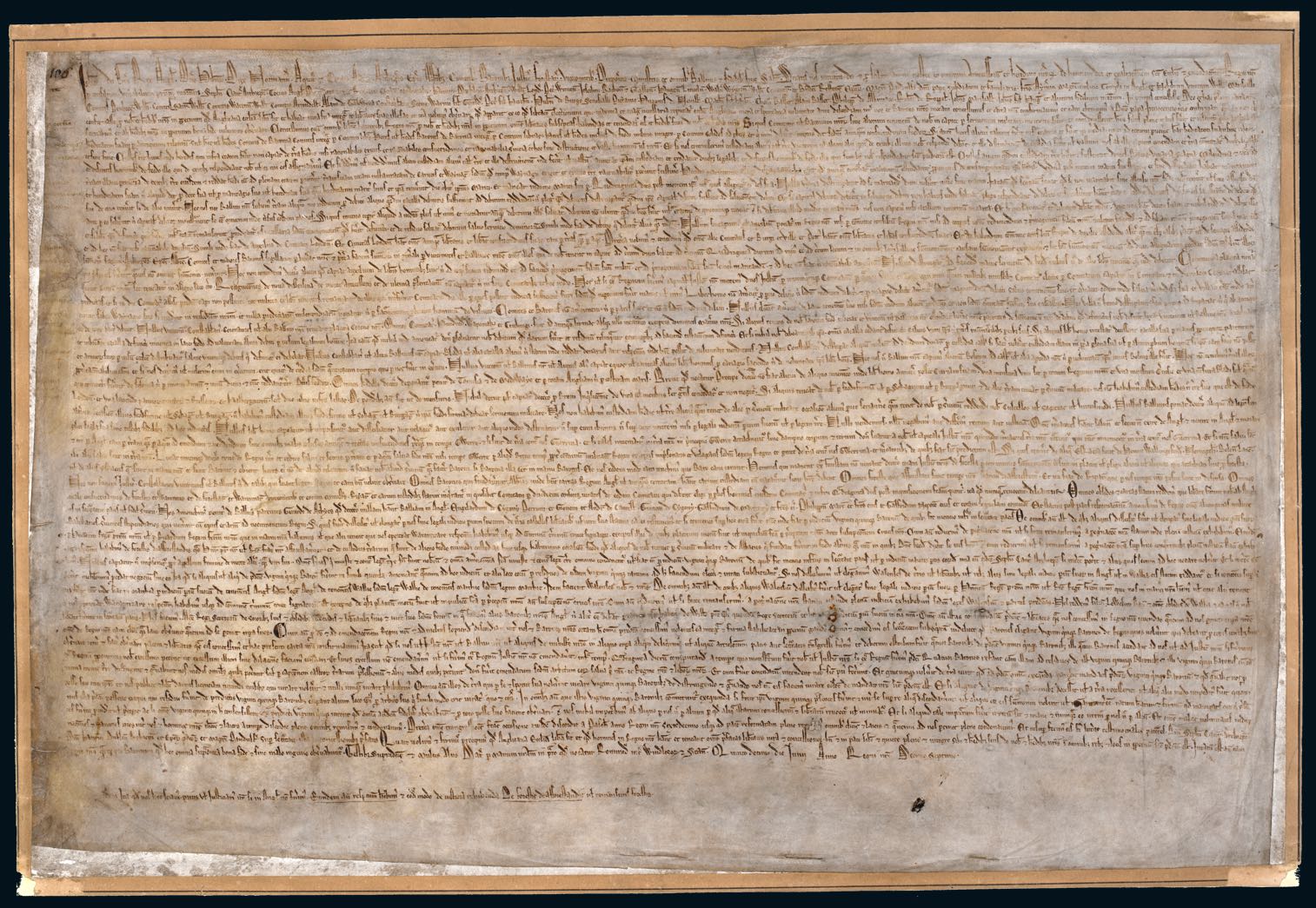

This meant that traditional British rights and liberties, many of which were traceable back to Magna Carta — such as the right to the law and a fair trial, to be considered innocent until proven guilty, to own property, and to sue for breach of contract — would be recognised in the new settlement right from the start.

But, for all this, colonists still lacked something fundamental: the right to make their own laws. The colony’s governor made the laws. He was free to raise road tolls and taxes, grant property and flog convicts without recourse to any parliament or, as Magna Carta’s Clause 14 puts it, to ‘the general consent of the realm’.

In 1803 Jeremy Bentham declared that this state of affairs was ‘repugnant to the constitution, [and] repugnant to Magna Charta’. It took more than two decades, but eventually Bentham’s view was vindicated. An 1823 Act of Parliament established a Legislative Council, which the governor consulted regarding new laws.