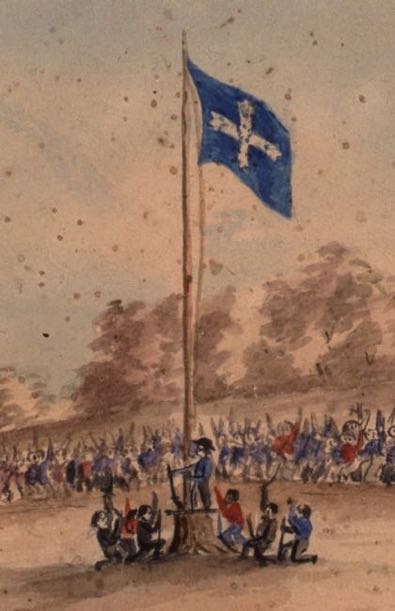

Eureka, 1854

Miners fighting for their rights

‘Taxation without representation is tyranny.’— Ballarat Reform League, November 1854

Gold was discovered in New South Wales and Victoria in 1851, and fortune–seekers from across the globe soon converged on the colonies. The two colonial governments issued mining licences which, as gold became more difficult to find, came increasingly to be seen by the miners as unjust. In Victoria, while the franchise was being extended to male property owners and some tenants, it was withheld from most miners. The government saw them as merely transient residents, with no land of their own. The miners had little say in how their lives were governed, and no say at all in how they were taxed. Violence and corruption in the administration of the goldfields led to agitation, arson and arrests.

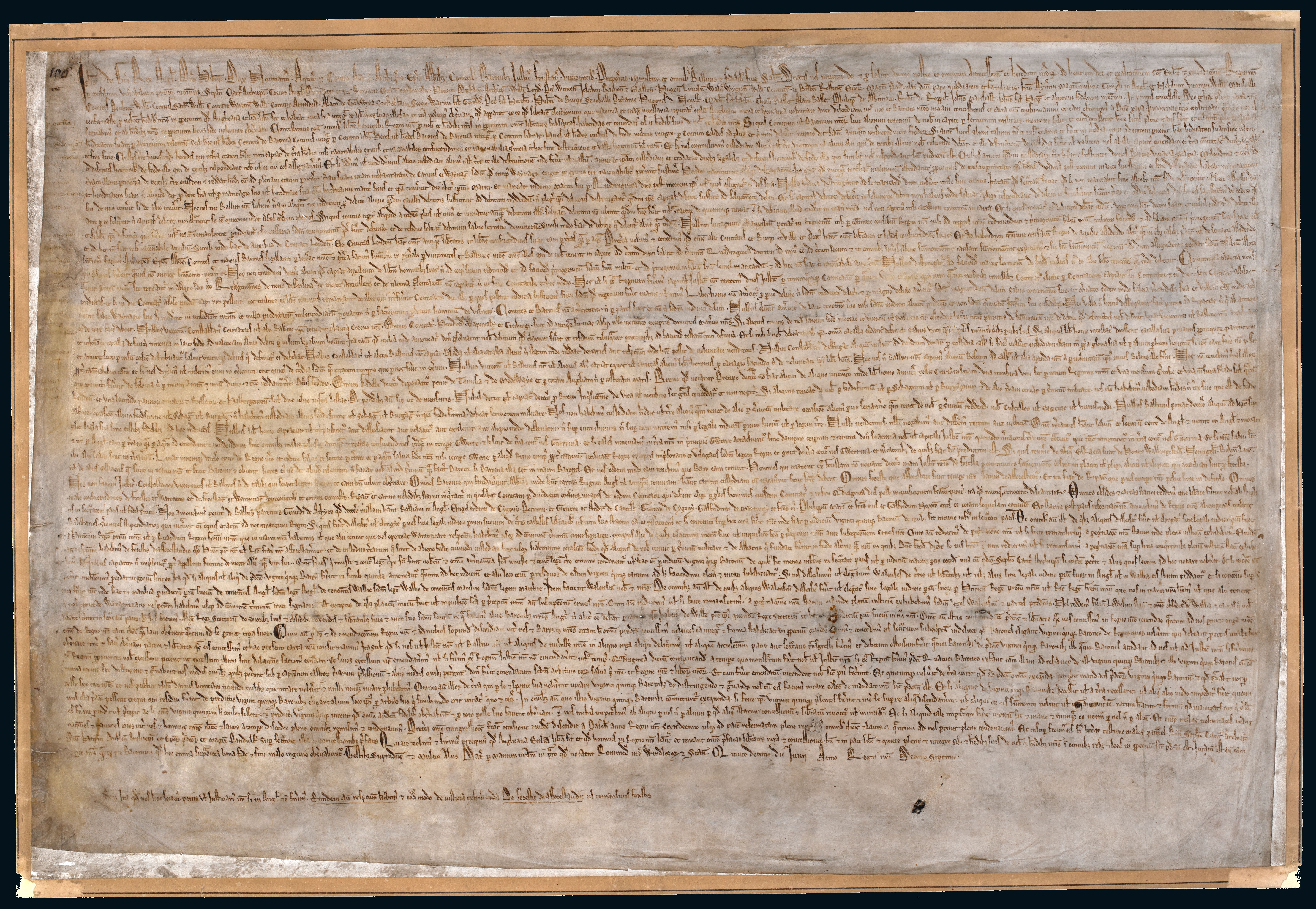

Things came to a head in Ballarat in 1854. In November a meeting of 10,000 miners, influenced by reformist ideas from Britain and elsewhere, loudly echoed Magna Carta when they declared it was ‘the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making all political power’. The miners organised themselves into a proto–rebel army, built a stockade and flew a new flag of independence, the Southern Cross.

The rebellion was smashed almost as soon as it had begun. Its ringleaders were arrested and put on trial for treason. But juries refused to convict. Within a year a new, cheaper form of mining licence had been issued. Most importantly, this new ‘Miner’s Right’ included the right to vote.