Communist Party Dissolution Act 1950

National security vs arbitrary government

‘The Great Charter … means, and it should always mean, in our democracies, first the rule of liberty. Secondly, it means that the rule of liberty is useless except under law. Thirdly, it means the hatred of arbitrary government or despotism.’— Dr H.V. Evatt, Leader of the Opposition, August 1952

The Communist Party Dissolution Act of 1950 outlawed what was seen as an actively revolutionary political party which sought, in the words of the Act’s preamble, ‘to bring about the overthrow … of government of Australia and the attainment of economic, industrial or political ends by force, violence, intimidation or fraudulent practices’.

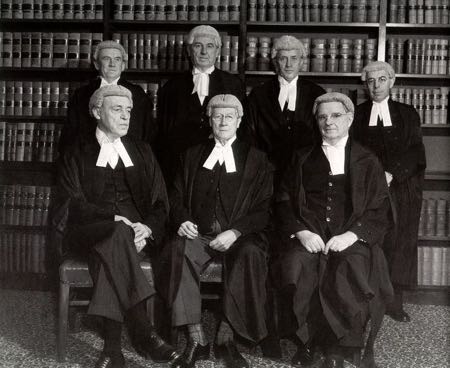

The Act placed the onus of proof on the accused: the Australian Communist Party and its affiliates. In Parliament, Opposition members had argued that this abolished basic rights, such as the right to know what one was being charged with, to defend oneself against accusation, and to have one’s case heard in public. The Communist Party and some trade unions, represented by a legal team that included Labor leader ‘Doc’ Evatt, took the Menzies Government to the High Court.

A majority of the judges decided that, although the government did in fact have the power to crack down on ‘sedition’ (incitement to rebellion), it was the job of the courts, not the government, to decide what actually constituted sedition. They ruled that the Act violated the Constitution and its principles, inherited from Magna Carta, which curtailed arbitrary power.

In response, Menzies took the decision to a referendum. Campaigning for a ‘No’ vote, Evatt denounced the Act as involving ‘the sacrifice of Magna Carta and the rule of law’. Against all expectations, the referendum proposal was rejected by the barest of margins.